Published Jul 17, 2019

Star Trek and Apollo 11 Broadcast Different Visions of the Future

'Assignment: Earth' is the perfect episode to watch on this moon-landing anniversary

StarTrek.com

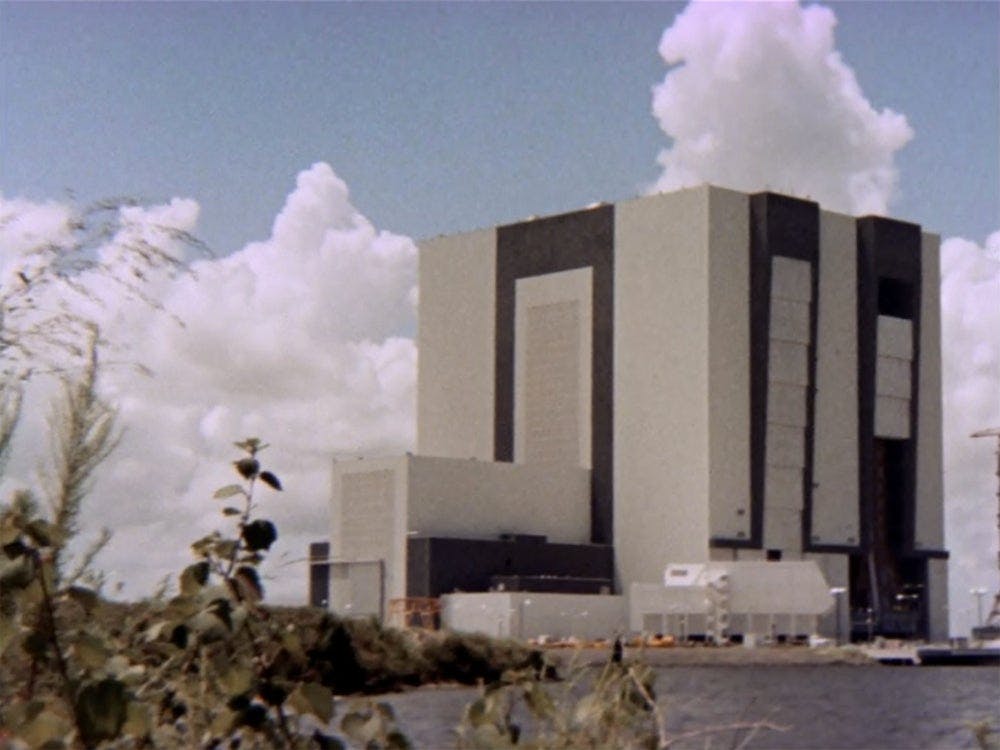

More than six months before the first crewed Apollo flight, the last episode of the second season of Star Trek: The Original Series, “Assignment: Earth,” was broadcast. The Enterprise time-travels to 1968 to observe earth in social and cultural turmoil. The transporter intercepts an alien agent, Mr. Seven, whose mission is to disrupt the launch of an orbital nuclear platform. Kirk has to decide if Seven is telling the truth––that preventing the launch will preserve the timeline in which the Enterprise exists –– or if he’s trying to sabotage earth’s future. The establishing shots of “McKinley Rocket Base,” are re-purposed footage of Kennedy Space Center, and film of the Saturn V launch vehicle (used for the Apollo lunar missions) stands in for the episode’s fictional rocket carrying nuclear warheads.

StarTrek.com

Before Apollo 11 successfully landed on the moon, watched by hundreds of millions of people around the world on live television, Star Trek offered a grim warning about the possible futures that spaceflight technology could bring about. The broadcast of the first moon landing and the debut of TOS are both iconic moments in 1960s television, but each represented very different visions of the future of human spaceflight.

This month marks the 50th anniversary of the first lunar landing, and 50 years since TOS went off the air. As part of the celebrations, the televised spectacle of Apollo 11 will be rebroadcast in many forms, from a real-time presentation on CBS of the network’s 1969 coverage to screenings at places like the Paley Center for Media. And, thanks to NASA’s YouTube channel, viewers can revisit that footage any time for free. The anniversary offers a moment of reflection on the role of the television broadcasts in visualizing the future of spaceflight.

The terrifying future that Mr. Seven averts in Star Trek would not have been outlandish for viewers in the 1960s. Nor would it seem strange, as it does to us today, to imagine the Saturn V moon rocket carrying nuclear weapons. The earliest rockets that carried astronauts into space were repurposed intercontinental ballistic missiles; Saturn was the first to be designed exclusively for human spaceflight. Before it was Kennedy Space Center, “America’s Spaceport” was the Atlantic Missile Range, adjacent to an Air Force base. Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin were both military pilots, and many of the engineers and administrators at NASA began their careers in the service. Added to lingering Cold War fears of nuclear war, the militarized space program in “Assignment: Earth” would have seemed perfectly plausible to viewers in the 1960s.

But the public’s understanding of the space program was also informed by the more Utopian aspects of science fiction. Concepts for orbiting luxury hotels and tourist flights to the moon appeared in science fiction magazines and books, as well as mainstream publications throughout the 50s and 60s, all alongside coverage of NASA’s growing program. In many senses it seemed that science fiction and science fact were converging and that a Star Trek-esque age of interplanetary exploration and adventure was beginning. For the broadcast of Apollo 11, science fiction was an integral part of the marathon coverage. CBS scheduled science fiction luminaries Arthur C. Clarke and Orson Welles to comment and contribute pre-recorded segments. ABC put together a panel moderated by The Twilight Zone’s Rod Serling, featuring Isaac Asimov. Combined with the colorful, dynamic graphics and model simulations developed by networks to fill in when there was no live footage, the real images of the lunar missions seemed technical and dry in comparison. The future would look like science fiction, it was simply a matter of choosing which version of that future to manifest. For some television viewers in 1969, that choice started to crystallize during the broadcast of Apollo 11.

There was abundant wonder to be had in the experience of watching the first lunar landing on television, even if it lacked the swashbuckling adventure, and technicolor aesthetics, of something like Star Trek. Just the act of broadcasting live television from the surface of the moon was a technological miracle, accomplished at great cost and utilized custom-built cameras and tracking stations as far-flung as Australia. Viewers also watched simulations created by the television networks, using models and sets, and listened to the voices of the astronauts being transmitted to earth via radio. On CBS, anchor Walter Cronkite and his guest host, retired astronaut Walter Schirra, expressed both childlike wonder and somber emotion for the audience.

During the spacewalk portion of the landing, networks showed the ghostly black and white figure of Neil Armstrong stepping onto the lunar surface for the first time, and both of the astronauts skipping across the face of the moon in an utterly unearthly motion. But after Armstrong had delivered his famous “One small step” line and Aldrin had joined him, the remainder of the 2 and a half-hour mission involved tediously collecting samples and setting up scientific experiments. The footage was grainy black and white, with strange effects present due to its slow-scan transmission, such as eerie ghosting and the image at one point appearing in negative. Once the warmth of Cronkite’s wonderment wore off, there was little drama available to keep viewers awake late into the night.

StarTrek.com

Although the CBS broadcast, in particular, remains a treasured historical artifact, television broadcasts of the moon landing were not universally loved at the time. Activist Jerry Rubin proposed that for the generation just coming of age at the end of the 1960s, neither the spectacle of television or the technological wonders of rocket launches were unexpected or particularly interesting. Those growing up in post-war America were presented with such marvels regularly. What was more, the aesthetics of NASA’s programs––cautious, conservative, technically meticulous, and helmed by men with buzz cuts and slide rules –– were unappealing to a generation raised on imaginative science fiction and radical politics.

The divergence between NASA and Star Trek also had to do with the ways that each could be experienced by ordinary people. For a moment in the summer of 1969, both existed as television programs, and both depicted a future where men explored outer space. NASA’s public relations relied on an understanding — one amplified by the science fiction writers who advocated for their programs — that the future they were making would eventually be for everyone (or at least for all Americans). Star Trek visualized this spacefaring future, taking the extra step of making sure that women and people of color were represented in ways they wouldn’t be for NASA for decades.

For the majority of Americans, the space program has remained a once in awhile spectacle, consumed through television specials or more recently livestreams and YouTube videos. Yet, Star Trek became a real-world phenomenon, capturing a level of public excitement that real space travel has yet to match. The Original Series went into syndication in the 1970s and grew a massive audience. In the last 50 years, there have been 13 films, seven new series, and countless real-life conventions, meetups, panel discussions and events in which fans can participate in the world of Star Trek in person. Real space travel remains the privilege of a few highly qualified astronauts or wealthy tourists who can afford multi-million dollar flights. Reduced to a few scientists growing lettuce on board the International Space Station and a rare viral video from orbit, the space program has shed much of the wonder and promise of the future that seemed to be beginning in 1969.

NASA

In “Assignment: Earth,” Mr. Seven is unable to prevent the launch of the nuclear weapons, and changes his plan to detonate the weapons in the atmosphere just close enough to teach humanity a lesson about the dangers of militarizing space. The decision to alter Earth’s past ultimately protects the future timeline in which the Enterprise exists. In the 1960s, as science fiction authors promoted the space program on television and Star Trek mapped out a Utopian future for exploration, it seemed that science fiction and science fact were converging. But Star Trek and Apollo 11 represented two diverging timelines in the future of spaceflight for a culture living in a world of political and social upheaval and lingering nuclear fear.

As viewers of the Apollo 11 broadcast were nodding off into the wee hours of the night in July 1969, Trek and American spaceflight, two of the most influential television spectacles of the 20th century, were already going their separate ways.

Anna Reser (she/her) is a historian of spaceflight and the co-founder of Lady Science. Follow her @annanreser.