Published Oct 27, 2020

A History of Star Trek's Gender Non-Conformity

From Jadzia Dax to Adira and Gray, all the times Star Trek has challenged societal gender expectations and binaries

StarTrek.com

With the exciting confirmation that Discovery is going to be home to new characters, the human, non-binary Adira (Blu Del Barrio), and the Trill trans man Gray (Ian Alexander), it’s a good time to examine the legacy of gender non-conformity in Star Trek.

Throughout its history, Star Trek’s surface-level depictions of gender have ranged from progressive to antiquated, but have not often risen above the core idea of male and female. However, by looking at some of the franchises’ more subversive which better echo society’s continuously expanding understanding of gender identity, we can find canonical arcs and storylines which current Star Trek shows could draw from.

StarTrek.com

Star Trek has approached queerness in a variety of ways, generally quite simplistically. While actors have had ideas about their characters' sexualities (including Andy Robinson, Alexander Siddig, Terry Farrell, Nana Visitor, Jeri Ryan, Jonathan Frakes, and more), the writing itself hasn't often corroborated that. When it has, it's been with mixed results.

The TNG episode “The Outcast” is arguably the first attempt to create a story about being gay (if we don't include fan-read subtext). Frakes has been vocal about wishing that Soren, the love-interest for Riker in that episode, had been played by a man, but many people have pointed out that Soren is put through conversion therapy because she identifies as a woman in a society that doesn't allow gender deviation. She can therefore be recognized as a transgender woman.

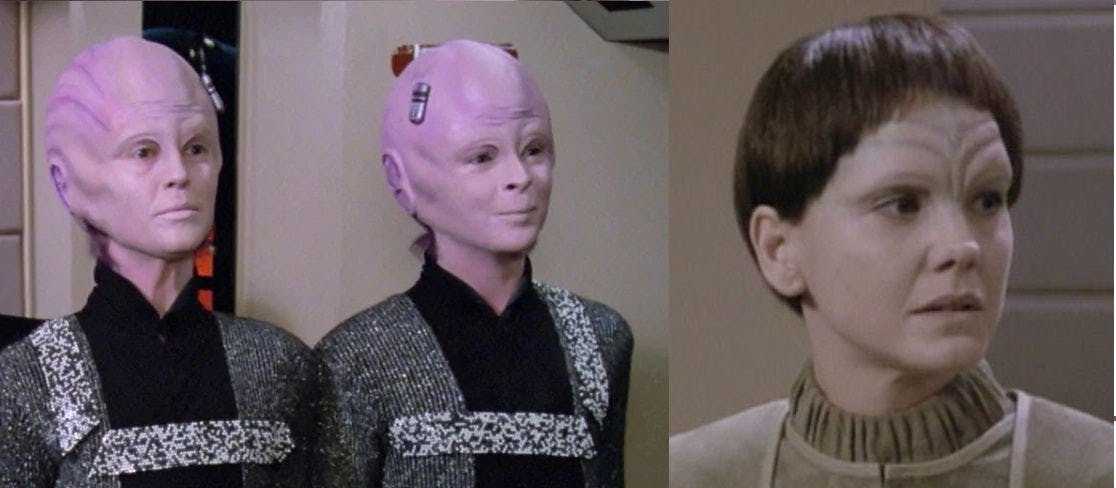

Similarly, in the first actual same-sex kiss on Star Trek (“Rejoined” from Deep Space Nine), we're given a gay allegory episode. The difference is that in this case two women kiss without any queer stigma. Although this was considered a step in the right direction, the lack of follow-through for same-sex representation felt like a missed opportunity for some fans.

Terry Farrell confirmed that she believes Jadzia was pansexual at Star Trek Las Vegas last year: “The only rule was ‘are you interesting to me, and do I want to know more about you?” Why wouldn't Trill lean more towards bi/pan/omni/polysexuality when the most sacred part of their society involves a genderless worm that creates a symbiotic relationship with various hosts?

What can also be inferred is that Trill – and especially joined Trill – must have entirely different ideas about gender and this difference makes Jadzia and Lenara another trans allegory couple, as well as a same-sex one. This is vaguely shown in TNG's introduction to the Trill, “The Host,” through a handful of lines by Jadzia and Ezri on DS9 that they have been both men and women, and further referenced in Ezri's inability to tell where she ends and her eight past hosts begin; she is, essentially, nine people of different genders at once. There isn't any exploration about what this might mean in terms of individual gender identity or on a structural basis for Trill society, but the implications are there for the taking.

None of this is new speculation. An article was written as early as 1997 that recognized the transgender undertones of the Trill. Ian Alexander playing the first explicitly trans Trill poses an interesting question of how the show will write trans identity in a species that already exists as a transgender allegory.

StarTrek.com

Between the aforementioned Trill, Changelings who can morph into any shape, gods who exist outside time and space, and an ongoing mini-storyline with a never-seen ensign — later lieutenant — named Vilix’pran who is assigned male pronouns and several times gives birth offscreen, Deep Space Nine is generally considered the queerest of the Treks.

Cardassians seem to have a binary that's underlined by what work you’re assigned to do by the state and blue make-up, which we see several Cardassian women wear, but also Garak in “The Way Of The Warrior.”

Ferengi gender subversion is directly linked to whether one can or cannot go into business. Considering this, can Pel (“Rules Of Acquisition”) be considered trans-masculine? Could Rom be trans-feminine? Several scenes – generally played for laughs – can easily be taken in that direction. Moreover it’s canon that gender reassignment surgeries can be obtained with ease, as seen in the otherwise tone-deaf “Profit and Lace.”

Despite this, the queerest of the Treks was never quite went the extra step to explore its own latent gender non-conformity.

StarTrek.com

There are other threads that explore gender through lenses that aren’t just alien. Between Borg, androids/synthetics, holograms, clones, and augments, there are more than enough examples of bio-engineering and A.I. that don’t fit the mould of traditionally gendered beings.

The Borg force people to assimilate into a seemingly genderless hivemind, with no say over their own individual bodies or minds. As this article about Seven of Nine explains, it's terrifyingly similar to what many transgender, intersex, and gender non-conforming kids in today's society have to go through. As a result of the trauma, characters like Seven of Nine and Hugh must figure out from an entirely different standpoint than Federation citizens what their relationships to their bodies are.

Good-natured but misunderstanding Voyager crewmembers try to help Seven “become more human.” But their attempts only underline that they need to be more understanding of other forms of engaging with one's sense of self, not that Seven is somehow less-than-human for her differences.

When we meet the xBs (ex-borg) in Star Trek: Picard, they are, according to Hugh, the most despised people in the galaxy. Their bodies are envied, destroyed, and otherwise objectified. This diminishing of a person’s self onto their body is familiar, both for people with “incorrect” bodies today and in the future.

Data's trial in “The Measure Of A Man” sounds very much like current trans and intersex-rights trials in which people are arguing to simply be allowed to exist, with all the dehumanizing language that comes with the so-called “debate.” By the time of Picard, androids are — like the xB — worse off than they were previously, with synthetics banned throughout the Federation for something that was done to them by organic species.

On Voyager the EMH/Doctor and other holograms are engaged in a similar struggle. “Flesh & Blood” serves as a memorable attempt to ask if holograms have their own form of sentience, and whether their use by their creators constitutes slavery. “Author, Author” further develops this idea by hinting at a future holographic uprising of some kind, although explored more through synthetics on Picard.

Storylines about holographic autonomy never seem to be afforded quite the same focus as that of androids/synthetics, and they’re not the only engineered group to suffer from lack of exploration.

The Dominion generals and soldiers, the Vorta and the Jem’Hadar, are gendered clone species, with the Vorta divided into two binaries and the Jem’Hadar strictly male. These species aren't given more than a handful of episodes that acknowledge that their personhood is curtailed by the Dominion and how they might redefine (or purposefully not redefine) the parameters of their bodies once the Dominion war is over.

All of these storylines show that even in the Star Trek universe, there can still be an “othering” of marginalized bodies. Those most recognizable as existing outside of society’s norms are often linked with fear — synthetics are banned, holograms who argue for autonomy are fanatics, clones work for the antagonists, and the Borg are, well, Borg. Society’s suspicions of them, even when the narrative favors the marginalized, is on some level justified. In the real world the so-called threat that non-conformity represents is not only fictional, but puts non-conforming people in danger.

StarTrek.com

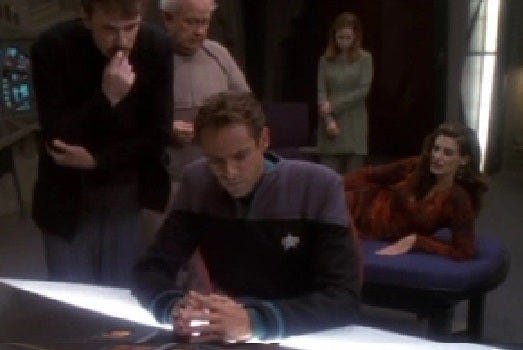

Yet another version of this is present in the writing for the augments. They were introduced in The Original Series’ “Space Seed” as bad guys, but their identities became more sympathetically handled through DS9’s Julian Bashir and the augments from the episodes “Statistical Probabilities” and “Chrysalis.” These characters were forcibly altered as children because they didn't fit with accepted normative society.

Augments aren't legally allowed to work in Starfleet and are generally institutionalized at a young age if discovered, but to what extent their lack of rights extends is unclear and is never significantly pursued either through Bashir or the other augments on the show. In fact, the show posits that society is right to fear them. While Khan may have been a legitimate threat in his day, there is no real indication that the later augments are anything but intelligent, disabled people who lack normative communication skills and are introduced as torturously sensory deprived individuals who thrive the second they’re given something to do.

Julian Bashir’s character is read as transgender by some fans for a number of reasons. The early-seasons overcompensation of performative masculinity when pretending he’s a Casanova (partially also read as his being neurodiverse and unable to read correct social behavior), the “passing” as a non-augmented human (again, heavily tied into outdated terminology directed at “high-” or “low-functioning” ND-people), the decision of the showrunners to give him shoulder-pads (what especially skinnier trans-masc hasn’t overthought their own shoulder-width?), and the interesting phrasing in “Body Parts” when he's forced to transfer the O'Briens' baby into Kira: “I had to find another womb for the baby and the only two people available were Major Kira and myself.”

In the real world the division between disability and gender is in some ways being eroded – many neurodiverse people identify as other gendered, specifically linking their gender to their neurodiversity (known as “neurogender”). When you see the world differently in one way, you’ll likely see it differently in many others too.

In light of that headcanon it's interesting to analyze Bashir’s gender identity as part of his status as an augment and as a character heavily coded as neurodiverse.

Consider Bashir's outburst to his parents in “Dr Bashir, I Presume:”

“You don't understand Jules. You never did.”

“No, you don't understand! I stopped calling myself Jules when I was fifteen and I'd found out what you'd done to me. I'm Julian!”

“What difference does that make?”

“It makes every difference! Because I'm different! Can't you see?”

Bashir's claiming of the name “Julian” in order to regain a sense of autonomy is as transgender as it gets. In fact, several characters on Star Trek already discussed in this article do the same thing for similar reasons.

The Doctor on Voyager tells Seven when she asks why he hasn't chosen a name in six years: “Choosing the right name for myself is extremely difficult. I'm a complex individual.” Meanwhile Seven herself rejects her given name “Annika,” and decides on the genderless Seven of Nine that she was known as in The Borg Collective. Hugh is “given” a name by Geordi that he resonates with and keeps for the rest of the show. Choosing a name, whether it be consciously settling on the one you were assigned with at birth or not, is a recognizable journey for many gender non-conforming people.

When discussing gender we are equally discussing all forms of marginalized bodies, people who don't “fit” with correct normative standards of what constitutes “man” and “woman,” — and the ways we are intentionally or unintentionally demonized in the universe of Star Trek.

StarTrek.com

Gender identity is increasingly becoming more nebulous and intersectional. In this world it's easier to see how more vague, less definable presentations of self are becoming more the norm, which fits in very well with the vagueness of these themes on the show itself.

Thus, my hope is that Discovery (and other current Trek shows) take the unique opportunity they have, as shows that take place so far in the future, to push today’s boundaries even further when it comes to discussions on queerness and gender.

Writers across the science fiction genre could stand to take a leaf out of Avery Brooks’ book and write trans, non-binary, and gender non-conforming identities in the same way that he was able to tackle being a Black man in the future: By acknowledging how important it is to see how far we might have come, as well as honoring the difficulties that we needed to overcome to get there. How can those of us who haven’t yet seen ourselves in humanity’s future not only imagine that we survive, but that we’re a vital, thriving part of it?

In the last trailer for Discovery season 3, there is some suggestion that the creators understand this. As Adira and Gray smile at one another and take each other’s hands, a voice-over states: “We all want a future that’s real. That matters.”

A Timeline Through the Star Trek Universe

Marlowe Mitchell (they/them) is an artist residing in London, UK. You can find them at @khuzd_belkul where they might rant about wanting to see a trans crustacean Lieutenant Villix’pran and his many kids.

Star Trek: Picard streams on Paramount+ in the United States, in Canada on Bell Media’s CTV Sci-Fi Channel and streams on Crave, and on Amazon Prime Video in more than 200 countries and territories.

Star Trek: Discovery streams on Paramount+ in the United States, airs on Bell Media’s CTV Sci-Fi Channel and streams on Crave in Canada, and on Netflix in 190 countries.